Mankind has had a long-standing obsession with death. We have philosophised over its implications and the possibilities brought about through its transition. Whole canons of literature have been written, expounding on its beauty, its finality and its mystery. All of our religions are founded on the idea that something exists after death and they each prescribe the sometimes very elaborate and ritualistic methods we use the world over for the treatment of the deceased.

Mankind has had a long-standing obsession with death. We have philosophised over its implications and the possibilities brought about through its transition. Whole canons of literature have been written, expounding on its beauty, its finality and its mystery. All of our religions are founded on the idea that something exists after death and they each prescribe the sometimes very elaborate and ritualistic methods we use the world over for the treatment of the deceased.

Archaeologists and historians assert that the custom of burying our dead is the oldest religious rite in our history. We’ve been committing the remains of our loved ones to the Earth for at least the last 100,000 years, and probably quite a bit longer. In fact, the habit of burying the dead is considered a primary indicator for measuring the development of primitive populations. Though we aren’t alone in this habit, both chimpanzees and elephants are known to bury or cover their fallen companions, though none do so with such pomp and circumstance as we.

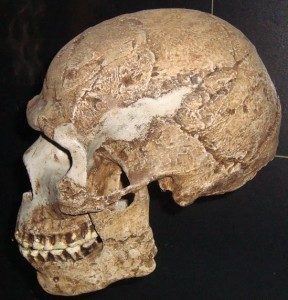

The earliest evidence of ritual interment was found in a cave called Es Skhul in Israel, on the slopes of Mount Carmel. Discovered somewhere between 1929 and 1932, the find at Skhul proved fruitful in anthropological terms, bearing 10 full human skeletons – seven adults and three children. The bones were covered in a red ochre and were accompanied by a variety of grave goods, from specific animal bones, like a boar’s mandible, to marine seashells. The remains and artefacts were dated to between 81,000 to 120,000 years old, and further study revealed that the skeletons were of a people who were the first to have the anatomical tools necessary for speech.

The earliest evidence of ritual interment was found in a cave called Es Skhul in Israel, on the slopes of Mount Carmel. Discovered somewhere between 1929 and 1932, the find at Skhul proved fruitful in anthropological terms, bearing 10 full human skeletons – seven adults and three children. The bones were covered in a red ochre and were accompanied by a variety of grave goods, from specific animal bones, like a boar’s mandible, to marine seashells. The remains and artefacts were dated to between 81,000 to 120,000 years old, and further study revealed that the skeletons were of a people who were the first to have the anatomical tools necessary for speech.

The Skhul remains, as well as the Qafzeh remains found in a cave in lower Galilee, which were found around the same time and were dated to approximately 92,000 years, are strong evidence that ritual burial became a feature of the early spiritual life of our ancestors over a period of decades and even centuries before 100,000 years ago.

Since then, we’ve complicated and serialised the process of dying. We’ve built monuments to commemorate it and churches to celebrate it. Today in America, death is a $15 billion industry, not including gravestones and monuments. Of the over two-and-a-half million people who die in the United States annually, a number that rises every year, more than half of them end up in a coffin or casket that ultimately gets buried in a cemetery plot. The rest are either cremated (and sometimes also buried) or are used for scientific or educational purposes.

Since then, we’ve complicated and serialised the process of dying. We’ve built monuments to commemorate it and churches to celebrate it. Today in America, death is a $15 billion industry, not including gravestones and monuments. Of the over two-and-a-half million people who die in the United States annually, a number that rises every year, more than half of them end up in a coffin or casket that ultimately gets buried in a cemetery plot. The rest are either cremated (and sometimes also buried) or are used for scientific or educational purposes.

The same isn’t necessarily true for the rest of the world though. While every human culture on Earth holds to some type of after-death ritual, such as burial or cremation, not all dead bodies end up six feet under.

Notwithstanding the various other methods of disposing of the dead, such as burial at sea and even pure neglect, some cultures have taken to stringing their dead up and hanging them from the side of mountains.

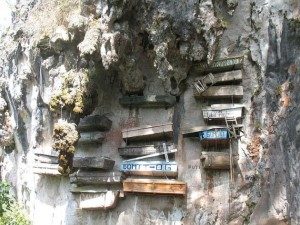

Enter the Mysterious Hanging Coffins of Sagada.

Sagada is a region in the Mountain Province of the Philippines, and in this area, as well as parts of Indonesia and China, local peoples have for centuries been hanging their deceased loved ones in ornate coffins from the mountain cliff sides. This is a tradition that originates with the ancient Bo people of southern China, and is still practised today.

Sagada is a region in the Mountain Province of the Philippines, and in this area, as well as parts of Indonesia and China, local peoples have for centuries been hanging their deceased loved ones in ornate coffins from the mountain cliff sides. This is a tradition that originates with the ancient Bo people of southern China, and is still practised today.

The coffins are traditionally carved out of a single log or piece of wood, often by the deceased during their lifetime. They are decorated ornately and painted, often in bright colours, and ultimately hung off of cliff faces, or in cave openings. Sometimes they simply sit on rock outcrops or are suspended by beams. Families have plots of rock face with a line of ancestors hung one above the other, though not everyone qualifies for this special type of burial. Depending on the region, these special burials were reserved for tribal elders or persons of spiritual significance, and others were required to have both children and grandchildren, as burial in this manner was/is thought to be of spiritual benefit to the younger generations.

It’s thought that this tradition may have begun as a way to reduce the risk of predation by animals and is a product of the terrain. Some of the coffins that can be seen on the cliffs at Echo Valley in Sagada are centuries old.

The funeral rites involve elaborate processions, often with the family carrying the corpse to the coffin at the hanging site. In these cultures, bodily fluids from the deceased were considered to be sacred and to contain the talent and luck of the deceased. If the procession carrying the corpse came into contact with such fluids, it’s thought to be a good omen.

The deceased would often be dressed in family colours and would be interred with spiritual belongings, and would traditionally be forced into a fetal position before the coffin was sealed. The dress and position, combined with the hanging of the coffin was believed to bring the deceased closer to heaven and offer a good vantage point from which to watch over their survivors.

The deceased would often be dressed in family colours and would be interred with spiritual belongings, and would traditionally be forced into a fetal position before the coffin was sealed. The dress and position, combined with the hanging of the coffin was believed to bring the deceased closer to heaven and offer a good vantage point from which to watch over their survivors.

The hanging coffins of Southeast Asia are a sight to behold, as is evidenced by the pictures, but it’s said that those who view these vertical graveyards in person are forever changed by the experience. From the perspective of Western society, these traditions may seem odd or even backward, but like any funerary ritual, they are deeply spiritual and engender powerful emotions for those involved. Our tradition of burying death under our feet could be said to create an out-of-sight-out-of-mind type of attitude toward our departed loved ones, but no matter what your personal leanings, there’s clearly no right or wrong way to say goodbye to those who have moved on to whatever awaits us all.