Why does the pursuit of Artificial Intelligence (AI) -the pursuit of artificially duplicating the complexity of the human brain- typically ignore the basic embryological facts of human cognitive development?

Edge.org, a self ascribed web 3.0 social experiment greatly contributed to by Editor and Author John Brockman, produces annually / semi-annually a thought provoking book based on a simple idea: Ask a profound question of the 100 greatest minds you can find and publish the result. The most recent incarnation of this effort is titled: This Will Change Everything (Edited by John Brockman), in which they’ve asked the simple question: “What will change everything? What game-changing scientific ideas and developments do you expect to live to see?”

There are some striking ideas in this book; some inspiring, unexpected and scientifically creative notions poke their heads through the stiff membrane of scientific supposition. There are some equally frightening, bland and even ignorant ideas as well (though, when one asks a silly question…). What’s particularly striking though is the popularity of the notion that AI will be the next major breakthrough for mankind. For various reasons and along various lines of logic, and with hugely varying timelines, among this group of 100 scientists, authors, philosophers, professors, and inventors, a great many have declared that AI will be our crowning achievement for the not-so-new-millennia. All of course with this one caveat; the human brain is so hugely sophisticated in terms of its computational power (read neural complexity, not an ability to compute like a PC), that the achievement of this power in an artificial environment requires the development of AI’s sister science, quantum computing, in order to succeed.

The human brain is simply too complex, and I would agree (with certain individual exceptions), however, man does not leap from the womb spouting prose and calculus; he is not readily a master of his intellectual domain. No, in fact many adults never reach the status of intellectual amateur, let alone master. And therein seems to lay at least a portion of the problem. Human development, be it cognitive or physical, is based entirely on cumulative embryological growth. Cell division, parlayed into tissue growth, parlayed into organ development, parlayed into sense memory and learning and cognition. It is not an instantaneous process, as though an infant’s perception of its strange new non-embryonic world was just suddenly switched on the moment the good doctor gave him a slap on the back.

No, cognitive development begins the very moment there is an opportunity for it, namely, when there is brain matter capable of supporting neural connections. Indeed, this happens very early in the embryonic development of all complex life. So, why then do AI researchers and computer development scientists, try to construct the baby full grown?

Embryology is, in my own humble words, a process of building on top of what you’ve already built. A foetus (or zygote or whichever particular embryonic label you prefer to use), human or otherwise, undergoes 6-18 months of gestation (generally speaking), a time during which its sensory input field is drastically reduced by way of its embryonic shield (the womb), allowing for uninterrupted development of the most basic cognitive processes -subconscious and autonomic processes and the like- the most necessary of which are ostensibly well developed by the time the creature is birthed into this cruel world of sensory overload. Obviously not a fool proof plan, but efficient enough as is evidenced by our current population.

Embryology is, in my own humble words, a process of building on top of what you’ve already built. A foetus (or zygote or whichever particular embryonic label you prefer to use), human or otherwise, undergoes 6-18 months of gestation (generally speaking), a time during which its sensory input field is drastically reduced by way of its embryonic shield (the womb), allowing for uninterrupted development of the most basic cognitive processes -subconscious and autonomic processes and the like- the most necessary of which are ostensibly well developed by the time the creature is birthed into this cruel world of sensory overload. Obviously not a fool proof plan, but efficient enough as is evidenced by our current population.

Then, of course, and depending on the particular species of animal we’re speaking of, comes years, decades or in some cases more than a century of further development. Continuous learning isn’t simply a Human Resources catch phrase; we quite literally are learning (read developing) new neural pathways and connections every second of every day.

The point of all this is, we, as in animals with functioning brains, do not spring into this world with much more than an operating system installed in this supercomputer of a cranium. So why do these AI developers think that their AI companions should be different? After all, they are trying to emulate a human brain.

It could be said that the developers haven’t the time to wait -decades or centuries as the case may be- though I would argue, time is one thing they have in abundance. There have been older generations of AI programming that have been analogous to foetal and/or infant neural capabilities, in one form or another, but as one reads more and more about the current direction and failings of AI research, it’s difficult not to come away wondering how they all missed it.

If one wants to construct an analog of a human brain, first start with an analog of a human brain in its earliest stage of development. From there, build on top of what you’ve already succeeded. Better yet, start by building an analog of a brain that is ten-fold more simple than a human brain, that of a chicken for example, and instead of simply mimicking the behaviour of the creature in question (as has already been done in the case of chickens), mimic its simplified neural systems and develop your engineering process from that simpler schematic.

I’m always impressed by the ability of scientific orators and their colleagues to use large numbers to simultaneously intrigue the learned onlooker and scare off the ignorant. However, I can scarcely remember reading an article on the development of AI that didn’t make use of the notion that there are millions of trillions of neural connections to account for in the adult human brain; impressive to be sure, though utterly meaningless to be equally sure. Pick up any scientific journal, magazine or periodical (providing it deals with computer science) and there will be at least one author explaining how closely related the successful development of AI is to the successful development of quantum computing; this as a direct result of the unfathomable number of neural connections that need to be mapped and interpreted. And, I offer no direct objection. Instead I offer an alternative. Stop trying to replicate the effect of a million trillion neural connections for a while…and start trying to replicate the effect of 100,000.

I’m certain there will be readers who will balk at the notion that the complexity of the human brain is irrelevant to AI research, and to be perfectly clear, I agree that the limitations of standard computer science are also the limitations of classic AI research. However, what I don’t agree with is the anthropocentric human ego which says, AI must, by definition, be equivalent to an adult human’s intelligence. Is it not, for the achievement, admirable enough to duplicate in every sense, into an artifice, the relative intelligence of an infant, or for that matter the relative intelligence of a dung beetle?

I’m certain there will be readers who will balk at the notion that the complexity of the human brain is irrelevant to AI research, and to be perfectly clear, I agree that the limitations of standard computer science are also the limitations of classic AI research. However, what I don’t agree with is the anthropocentric human ego which says, AI must, by definition, be equivalent to an adult human’s intelligence. Is it not, for the achievement, admirable enough to duplicate in every sense, into an artifice, the relative intelligence of an infant, or for that matter the relative intelligence of a dung beetle?

Yes, there already are many examples of bug-robots roaming all over robotics labs around the world, though these are specifically not examples of AI for two reasons. The vast majority of these bug-robots mimic only the behaviour of its biological counterpart (hence being called robots), and no part of the creatures brain function has even been considered in its design. Would it not be a remarkable achievement, even in the shadow of mainstream AI research, for computer scientists to map, engineer, design and build a bug brain? And would not such an achievement constitute at least a small step forward in AI research?

Bugs, of course are just one example of the huge genome of animals available to act as a model for this mannequin chiselling, and though I concede that there are many other seemingly insurmountable issues to be considered by AI researchers, not the least of which is identifying exactly how memory is stored in brain matter, I’m speaking only of the heralded obstacle AI researchers and their compatriots themselves have identified as their biggest hurdle.

This of course, is about to digress into a discussion about the meaning of intelligence and sentience; is a dung beetle intelligent, by any standard? Some would answer yes (as would I) and others would answer no, then others still would insist on dragging arguments for a soul into the mix, and much as I’m clear on my own opinion, I have no interest in hearing everyone else’s, not at the moment at least.

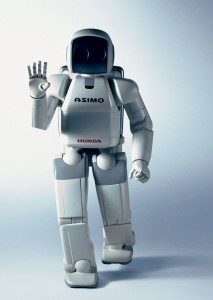

So, even as these are not the romantic issues offered by a typical discussion of AI –like the ethical implications of creating sentience, and/or (as Hollywood would have us focused) on the possible long term ramifications of providing machines with the ability to reason– there is, I think, little to fear from the laboratories of AI researchers, not for a great while at least. Our culture (western culture that is) is replete with failed notions of futurology. It seems we have a penchant for projecting both our best hopes and worst fears on the future, and as always, the reality of that future unfailingly lands somewhere in the middle. We are no more now like Stanley Kubrick’s vision of what ten years ago should have been, than we are like the Jetsons. And whether you agree with the ethical, moral and humanistic elements of AI research or not, it stands to reason that you won’t have all that much longer to wait for some incarnation of a thinking and feeling robot in the lab and on the street.

Buy a copy of John Brockman’s book, This Will Change Everything in Paranormal People’s Amazon.com Book Store.