Among the megalithic structures of the ancient world, from huge pyramid complexes that boggle the mind, to rock walls consisting of precisely carved and placed stones of almost unimaginable size, to mysterious and beautiful stone circles, our history is rich with examples of ancient artistry and ingenuity.

Among the megalithic structures of the ancient world, from huge pyramid complexes that boggle the mind, to rock walls consisting of precisely carved and placed stones of almost unimaginable size, to mysterious and beautiful stone circles, our history is rich with examples of ancient artistry and ingenuity.

Much speculation exists surrounding quarry and construction methods, and the ultimate purpose of these types of sites around the world is largely shrouded in mystery. Locations like Teotihuacan in Mexico, or Petra, the stone city of Jordan have been studied for centuries by both the professional and the amateur. Entire volumes have been written providing exacting descriptions and academically based analysis. But some places, like Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, seem to defy clear explanation.

Stonehenge itself has been the focus of much speculation over the years, but recently several new theories have surfaced regarding its original purpose and common use through the ages. As mentioned in my recent post New Stonehenge Theory Unveiled, research conducted by the University College, London’s resident Stonehenge expert Mike Pearson, suggests that Stonehenge was originally a massive burial ground that eventually turned into a venue for mass celebrations.[1] These conclusions add to the long held idea that the site was used, via bi-annual pilgrimage, as a ceremonial site in honour of the changing seasons and the passing of important figures in wider society.

Stonehenge doesn’t stand on its own, however. In Britain alone there are approximately 1400 Neolithic stone circles, globally that number may be as high as 5000. So much attention has been given to Stonehenge that many people are surprised to find that henges are so common in both Europe and Asia, and that even North American Indian tribes were known to construct standing stone circles.

Some of the more spectacular examples are:

Castlerigg Stone Circle – Characterised by archaeologist John Waterhouse as “one of the most visually impressive prehistoric monuments in Britain.” Located near Keswick in Cumbria, North West England, Castlerigg is known as the most visited stone circle site in Cumbria, of which there are several. Antiquarian studies suggest that it was built in approximately 3200 BC (late Neolithic), making Castlerigg one of the oldest known stone circles in Europe, which in turn makes it a very important archaeological site. Interestingly, Castlerigg is believed to have been an important part of the Neolithic Langdale axe industry and may have been used as a sort of marketplace for the trading of axes and other such wares.[2] Today, much like Stonehenge, Castlerigg is used by pagan groups in solstice celebrations due to its celestial alignments.

Rollrite Stones – Actually three distinct Bronze Age Neolithic monuments, the Rollrite Stones consist of The King’s Men, The King Stone and The Whispering Knights. The three sites are located near the village of Long Compton on the border of Oxfordshire and Warwickshire in the English Midlands. The Whispering Knights, a dolmen (a single chamber megalithic tomb), was the first to be built in approximately the 2nd millennium BCE, with The King’s Men following somewhere between the 2nd and 4th millennium BCE. The King’s Men is a stone circle believed to have trade based origins, much like Castlerigg, acting as a meeting place or market. The King Stone, located just north of The King’s Men, is a single standing stone of unknown date. It is believed to have been a marker for or a component of a Long Barrow or other burial site, but there is some speculation as to its alignment to the stone circle. The Rollritte Stones, especially The King’s Men, are an important site for neo-pagan magico-religious rituals.

Rollrite Stones – Actually three distinct Bronze Age Neolithic monuments, the Rollrite Stones consist of The King’s Men, The King Stone and The Whispering Knights. The three sites are located near the village of Long Compton on the border of Oxfordshire and Warwickshire in the English Midlands. The Whispering Knights, a dolmen (a single chamber megalithic tomb), was the first to be built in approximately the 2nd millennium BCE, with The King’s Men following somewhere between the 2nd and 4th millennium BCE. The King’s Men is a stone circle believed to have trade based origins, much like Castlerigg, acting as a meeting place or market. The King Stone, located just north of The King’s Men, is a single standing stone of unknown date. It is believed to have been a marker for or a component of a Long Barrow or other burial site, but there is some speculation as to its alignment to the stone circle. The Rollritte Stones, especially The King’s Men, are an important site for neo-pagan magico-religious rituals.

The Ring of Brodgar – (Also Brogar or Ring o’ Brodgar) The third largest stone circle in the British Isles and the youngest monument on the Ness o’ Brodgar, The Ring of Brodgar is believed to have been built between 2500 BCE and 2000 BCE. It has typically defied traditional dating techniques, and as the centre of the circle has never been excavated, little is known about its true age and purpose. The Ring sits in the West Mainland parish of Stenness, on Orkney Isle in Scotland. Among several other Neolithic sites in Orkney, The Ring of Brodgar enjoys protection as a World Heritage Site under the Heart of Neolithic Orkney. The site’s caretakers from Historic Scotland describe the site as “…the finest known truly circular late Neolithic or early Bronze Age stone ring and a later expression of the spirit which gave rise to Maeshowe.”[3]

The Ring of Brodgar – (Also Brogar or Ring o’ Brodgar) The third largest stone circle in the British Isles and the youngest monument on the Ness o’ Brodgar, The Ring of Brodgar is believed to have been built between 2500 BCE and 2000 BCE. It has typically defied traditional dating techniques, and as the centre of the circle has never been excavated, little is known about its true age and purpose. The Ring sits in the West Mainland parish of Stenness, on Orkney Isle in Scotland. Among several other Neolithic sites in Orkney, The Ring of Brodgar enjoys protection as a World Heritage Site under the Heart of Neolithic Orkney. The site’s caretakers from Historic Scotland describe the site as “…the finest known truly circular late Neolithic or early Bronze Age stone ring and a later expression of the spirit which gave rise to Maeshowe.”[3]

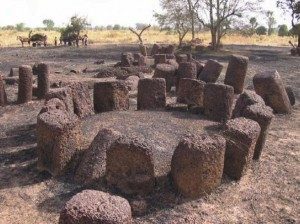

The Senegambian Stone Circles– Actually a collection of four large groups of stone circles, the Senegambian Stone Circles consist of over 1000 individual circles spread out over an area of approximately 15,000 square miles in and around Gambia, Senegal. Unlike some stone circle monuments in Western Europe, the Senegambian Stone circles, which were built around the eighth century, almost unanimously mark ritualistic burial sites. The circles were built by the ancestors of the Serer people of Senegal and have some connection to the steles of Roog, the supreme deity of the Serer religion. Also appearing on the World Heritage List, UNESCO describes the collection as “…a vast sacred landscape created over more than 1,500 years. It reflects a prosperous, highly organized and lasting society.”[4] Interestingly, people of the area are known to leave small stones on top of the standing stones as a part of some unknown tradition.

The Senegambian Stone Circles– Actually a collection of four large groups of stone circles, the Senegambian Stone Circles consist of over 1000 individual circles spread out over an area of approximately 15,000 square miles in and around Gambia, Senegal. Unlike some stone circle monuments in Western Europe, the Senegambian Stone circles, which were built around the eighth century, almost unanimously mark ritualistic burial sites. The circles were built by the ancestors of the Serer people of Senegal and have some connection to the steles of Roog, the supreme deity of the Serer religion. Also appearing on the World Heritage List, UNESCO describes the collection as “…a vast sacred landscape created over more than 1,500 years. It reflects a prosperous, highly organized and lasting society.”[4] Interestingly, people of the area are known to leave small stones on top of the standing stones as a part of some unknown tradition.

Stone circles are a prevalent aspect of ancient human culture, and while they still largely represent a historical mystery, it is clear that nearly every ancient culture on earth has constructed megalithic monuments of some kind or another throughout their development. The purpose of each site is often unique to its location, whether Britain, or France, or China, or the western plains of Canada and the US. But the construction of such monuments always represented an advancement in the evolution of local culture.

As with most ancient megalithic constructions, certain groups, such as the Ancient Alien Theorists, claim that our understanding of these sites is limited by the narrow view of the establishment that is science. And while many neo-pagan sects today lay claim to many of these sites as spiritually significant in their practises, the available evidence strongly points to much more pedestrian and mundane origins for these stone circles and other monuments. Whether these connections to a spiritualist origin are justified or not, the by-product of their continued use for spiritual purposes and the typical reverence afforded the sites in turn serves, with some exceptions, to aid official efforts to preserve them for future generations.

[1] BBC News UK. Stonehenge builders traveled from far, say researchers. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-21724084

[2] Rodney Castleden, Neolithic Britain: new stone age sites of England, Scotland, and Wales. Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0415058457.

[3] “The Heart of Neolithic Orkney”. Historic Scotland

[4] Stone Circles of Senegambia – UNESCO World Heritage Centre: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1226

In the world of UFOlogy and Cryptozoology few characters are as spooky and memorable as those associated with the Derenberger incident. And while many people may be unfamiliar with the case itself, the characters involved are infamous, both among paranormal circles and in popular culture.

In the world of UFOlogy and Cryptozoology few characters are as spooky and memorable as those associated with the Derenberger incident. And while many people may be unfamiliar with the case itself, the characters involved are infamous, both among paranormal circles and in popular culture.

But his story doesn’t end there, and neither does Woodrow Derenberger’s. Following the events of Point Pleasant, Derenberger made claims that Cold had admitted, through continued telepathic contact, that he was an alien from a planet called Lanulos within the galaxy known as Genemedes (both of which seem to be fictional). More than that, however, Derenberger claimed that Cold had actually taken him to Lanulos in a spaceship, where Derenberger claimed to have seen many other Lanulosians and relayed some commentary on their culture. Over the years, according to Derenberger, Cold was joined on earth by two other Lanulosians, named Demo Hassan and Karl Ardo, both of whom were apparently more discreet than Cold ever was.

But his story doesn’t end there, and neither does Woodrow Derenberger’s. Following the events of Point Pleasant, Derenberger made claims that Cold had admitted, through continued telepathic contact, that he was an alien from a planet called Lanulos within the galaxy known as Genemedes (both of which seem to be fictional). More than that, however, Derenberger claimed that Cold had actually taken him to Lanulos in a spaceship, where Derenberger claimed to have seen many other Lanulosians and relayed some commentary on their culture. Over the years, according to Derenberger, Cold was joined on earth by two other Lanulosians, named Demo Hassan and Karl Ardo, both of whom were apparently more discreet than Cold ever was. Keele believed that the first ever encounter with The Grinning Man occurred in Elizabeth, New Jersey on October 11, 1966, less than a month before Derenberger’s encounter. On that night two young boys, Martin Munov and James Yanchitis were walking home along a road that ran adjacent to the elevated New Jersey Turnpike. As they walked along the dark street, Yanchitis noticed a strange looking man standing in the darkness at the top of the treacherous incline, trapped by a chain link fence. Upon calling out to Munov, the boys watched as the figure slowly turned to face them with an unnerving ear to ear grin.

Keele believed that the first ever encounter with The Grinning Man occurred in Elizabeth, New Jersey on October 11, 1966, less than a month before Derenberger’s encounter. On that night two young boys, Martin Munov and James Yanchitis were walking home along a road that ran adjacent to the elevated New Jersey Turnpike. As they walked along the dark street, Yanchitis noticed a strange looking man standing in the darkness at the top of the treacherous incline, trapped by a chain link fence. Upon calling out to Munov, the boys watched as the figure slowly turned to face them with an unnerving ear to ear grin.

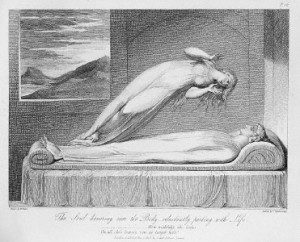

Some try to frame their hypotheses in the language of science, of physics, such as the Quantum Theory of Ghosts developed by Max Bruin PhD., which says that ghosts are “an impression upon the subatomic weave of the universe, created via strong emotion of a sentient observer.”

Some try to frame their hypotheses in the language of science, of physics, such as the Quantum Theory of Ghosts developed by Max Bruin PhD., which says that ghosts are “an impression upon the subatomic weave of the universe, created via strong emotion of a sentient observer.” Recent discussion on the existence of the soul and the ramifications of a conclusion in either direction – such as you can find

Recent discussion on the existence of the soul and the ramifications of a conclusion in either direction – such as you can find  László isn’t alone in this line of thought however. Laid out in his 1994 book, Shadows of the Mind,

László isn’t alone in this line of thought however. Laid out in his 1994 book, Shadows of the Mind, It turns out though, that wave function collapse doesn’t explain the process, at least according to Swedish-American physicist and cosmologist Max Tegmark. Tegmark argued in his 2000 paper in the journal Physical Review E, that wave function collapse would occur at too fast a rate for it to have any impact on neural processes.

It turns out though, that wave function collapse doesn’t explain the process, at least according to Swedish-American physicist and cosmologist Max Tegmark. Tegmark argued in his 2000 paper in the journal Physical Review E, that wave function collapse would occur at too fast a rate for it to have any impact on neural processes.

How would you react to seeing an exact duplicate of someone you love? Would you be able to tell which was which? Who is the real one and who is the…imposter?

How would you react to seeing an exact duplicate of someone you love? Would you be able to tell which was which? Who is the real one and who is the…imposter?

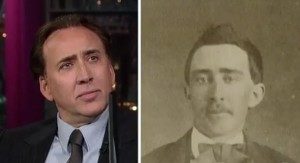

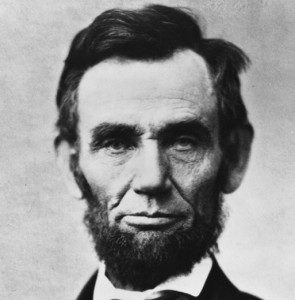

Other famous accounts of Doppelgänger encounters, like that of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and even Abraham Lincoln – who saw himself in a mirror sporting two faces

Other famous accounts of Doppelgänger encounters, like that of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and even Abraham Lincoln – who saw himself in a mirror sporting two faces Interestingly, the many-worlds theory of quantum physics, or the many-worlds interpretation may actually support this idea. The many-worlds theory says that through universal wavefunction, all possible histories and futures exist simultaneously. This is different from the multiverse theory, as the latter is the assertion that outside of our physical universe exist many other universes, possibly with differing laws of physics.

Interestingly, the many-worlds theory of quantum physics, or the many-worlds interpretation may actually support this idea. The many-worlds theory says that through universal wavefunction, all possible histories and futures exist simultaneously. This is different from the multiverse theory, as the latter is the assertion that outside of our physical universe exist many other universes, possibly with differing laws of physics.