In the world of weird there are many places that elicit wonder and trepidation. Aside from the usual haunted locals that many think of, there are many geographical locations that embody mystery, the Bermuda Triangle for one. Though if there were an election for the capitol of weird, one location would be at the top of the list of consideration: The Ural Mountains.

The Urals, as they are commonly known, are a mountain range stretching north and south through western Russia. The iconic region ranges from the coast of the Arctic Ocean in northern Russia to the borders of Kasakhstan in the south. It marks the northern border between the continents of Europe and Asia and is a treasure trove of geological bounty and historical significance. Its highest peak, Mount Narodnaya, sits at 6,217 feet.

Like many mountainous regions, the Ural Mountains have their share of strange stories and mysteries, but perhaps the strangest story to come out of the area is that of the Dyatlov Pass Incident.

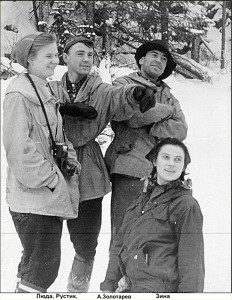

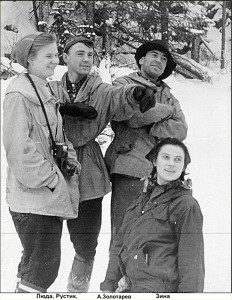

In mid January 1959, a group of young skiers embarked on a trip into the frozen wilds of Kholat Syakhl, a mountain in the northern Ural range, commonly known as The Dead Mountain (the name Kholat Syakhl means dead mountain in Mansi, the dialect of the local Mansi people, and refers to the lack of wildlife on the mountain). Nine of the ten members of the group hiked into the mountains headed for the slopes of Otorten (one member, Yuri Yudin, fell Ill early on and was forced to turn back). On February 1st, the experienced group, led by Igor Dyatlov (after whom the mountain pass was eventually named) strayed from their planned route, probably because of poor weather conditions, and found themselves on a high slope of Kholat Syakhl, where they decided to camp overnight.

The events of that night are not well understood, but judging by the aftermath, whatever happened, it was one hell of a night.

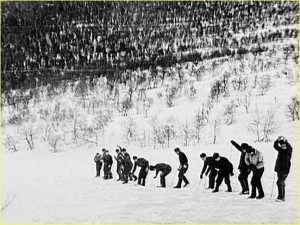

Deduced from intensive search and rescue effort and subsequent investigation, the early morning hours of February 2nd 1959 were tragic and eventful. Search efforts, which were initiated on February 20th found an eerie scene. The camp was found on February 26th and it was quickly determined that something bad had happened. A tent was found and it appeared that whomever had been inside had torn their way out of it…from the inside.

Footprints were found leaving the camp, unfortunately, these footprints showed that the hikers were either barefoot, wearing socks or only one shoe. Fearing the worst, search teams upped the intensity of their search and eventually found the first of the group, Yuri Krivonischenko and Yuri Doroshenko, huddled around the base of a large cedar tree just more than a kilometer from the campsite; frozen, shoeless and dressed only in their underwear. The remains of a fire were found nearby, but the -30 degree climate and high winds would not have been staved off by a fire alone.

Next to be found were Dyatlov, Zina Kolmogorova and Rustem Slobodin. All three were found part way between the camp and the cedar tree, in poses that suggested that they were attempting to return to the tent when the elements overtook them.

The other four members, Semyon Zolotariov, Nicolai Thibeaux-Brignolles, Ludmila Dubinina and Alexander Kolevatov, weren’t found for another two months. They were eventually found under four meters of snow in a ravine 75 meters beyond the cedar tree. It appeared that these four had survived longer than the previous five, as it seemed that they had taken clothing from their fallen comrades in an effort to survive.

All in all, it seemed apparent that the group had succumbed to the elements, but further investigation generated a host of questions. Why had they left the warmth and safety of their tents? Why had they ventured out without their clothing or shoes? And why did they not attempt to recover their belongings after leaving the camp?

These compelling questions further drove the investigation and very few answers seemed to emerge.

Early on, the official cause of death for the entire group was listed a hypothermia, but following a more thorough assessment of their injuries, investigators found that two of the group members had fractured skulls and two had severe chest trauma resulting in several broken ribs. One of the women, Ludmila Dubinina, was missing her entire tongue. One Dr. Boris Vozrozhdenny estimated that the force required to inflict the chest wounds would have been similar to a severe car accident, but what baffled investigators was the fact that there were no external wounds. No cuts, scrapes, bruises or other visible trauma.

Theories and speculation began to circulate; some people thought that perhaps an avalanche had struck the camp after lights out, though there was no sign of avalanche damage anywhere near the camp. Others thought that the local Mansi people had happened upon the group and took exception to them trespassing on their land, and had slaughtered them in the night. This of course, makes little sense, as the Mansi are not territorial in this manner and have no history of such behaviour, nor could such an attack have accounted for the type of injuries found…no superficial or external wounds.

What is perhaps the most baffling part of the story is the fact that the clothing of some of the deceased showed radioactive contamination at higher levels than would be found naturally. Though skeptics have correctly pointed out that some camping lanterns use Thorium gas mantles, which can leave radioactive residue on clothing and other items in their general proximity, but who knows if the levels found were consistent with that of Thorium mantles.

Many theories, some more credible than others, have surfaced over the years, but the fact that there were no survivors or eyewitnesses drastically impeded the investigation, which was officially closed in May of 1959. Investigators cited the “absence of a guilty party” for their laughable conclusion that the group members had died due to a “compelling natural force”. The local government also imposed a ban on anyone seeking to camp or even travel through the area, which lasted for more than three years.

Many theories, some more credible than others, have surfaced over the years, but the fact that there were no survivors or eyewitnesses drastically impeded the investigation, which was officially closed in May of 1959. Investigators cited the “absence of a guilty party” for their laughable conclusion that the group members had died due to a “compelling natural force”. The local government also imposed a ban on anyone seeking to camp or even travel through the area, which lasted for more than three years.

Since then, others have come forward with further information, such as another group of hikers who camped approximately 50 kilometers south of the Dyatlov group, claimed to have seen several large orange glowing orbs in the general direction of Kholat Syakhl on that evening. It was also found that the area of the Dyatlov camp was directly in the flight path of intercontinental R-7 missile test launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome (though it’s not clear if there had been any test launches on that night). Some have claimed that there had been an inordinate amount of scrap metal of unknown origin in the vicinity of Kholat Syakhl, and that the Russian government was/is complicit in a cover-up of illegal military dumping.

Few have come right out and said it, but there is the obvious possibility of UFO or alien influence in this case, and though that may seem far-fetched, it remains clear that the members of the Dyatlov group were subjected to a terror that caused them to act in a most irrational and ultimately fatal manner. These experienced hikers put aside common sense and fled the safety of their camp, knowing that the elements were likely to kill them. Why would someone do that, unless the prospect of staying (or returning) was more frightening and dangerous than braving the frigid night?

“If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.” Whether it was Feynman, Einstein or Vonnegut who actually said it (if any of them), Dawkins has certainly taken it to heart.

“If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.” Whether it was Feynman, Einstein or Vonnegut who actually said it (if any of them), Dawkins has certainly taken it to heart.

Everything you experience is in the past. In fact, the nature of reality dictates that everything you will ever experience, everything you can experience will have already happened by the time you experience it.

Everything you experience is in the past. In fact, the nature of reality dictates that everything you will ever experience, everything you can experience will have already happened by the time you experience it. So, in case you slept through high school science class, that means that all you can ever see of the stars in the night sky, is their past. Their distant past in most cases. In some cases we’re talking about billions of years distant.

So, in case you slept through high school science class, that means that all you can ever see of the stars in the night sky, is their past. Their distant past in most cases. In some cases we’re talking about billions of years distant. Even over a distance of a few feet it still takes time for the light to travel from the bulb to the wall, where the wall’s surface, depending on its colour, absorbs all but a very narrow band of the spectrum, and the light is then reflected away from the wall and into your eye. This is where it impacts the special cone shaped cells that line your retina, and you see it. This all happens in a very short fraction of a second, depending on the size of the room, but rest assured, it happens constantly, everywhere…in every room with a light bulb that is turned on.

Even over a distance of a few feet it still takes time for the light to travel from the bulb to the wall, where the wall’s surface, depending on its colour, absorbs all but a very narrow band of the spectrum, and the light is then reflected away from the wall and into your eye. This is where it impacts the special cone shaped cells that line your retina, and you see it. This all happens in a very short fraction of a second, depending on the size of the room, but rest assured, it happens constantly, everywhere…in every room with a light bulb that is turned on. Let’s stick with light for the time being. After that light jumps through all the hoops I laid out above, it does indeed strike the back of your eye. It’s collected by those little cone shaped cells on your retina (there are also rod shaped cells, which do the same thing, in a slightly different way, but this isn’t important to this discussion). Those little cones do a little magic (not really) as they convert the different wavelengths of light and the varying brightness of that light into a complex series of electrical impulses that travel up the optic nerve, through the back of the eye and into the visual cortex of the brain. There, those electrical impulses are sorted and correlated with a whole library of memories and the entire jumbled mess is converted into an image. Not like a jpeg or something. Well, actually, it’s a little like a digital image, but that’s another story.

Let’s stick with light for the time being. After that light jumps through all the hoops I laid out above, it does indeed strike the back of your eye. It’s collected by those little cone shaped cells on your retina (there are also rod shaped cells, which do the same thing, in a slightly different way, but this isn’t important to this discussion). Those little cones do a little magic (not really) as they convert the different wavelengths of light and the varying brightness of that light into a complex series of electrical impulses that travel up the optic nerve, through the back of the eye and into the visual cortex of the brain. There, those electrical impulses are sorted and correlated with a whole library of memories and the entire jumbled mess is converted into an image. Not like a jpeg or something. Well, actually, it’s a little like a digital image, but that’s another story. OK, here it is. That process, like the speed of light itself, happens almost instantly…almost. It does take a certain amount of time for those little electrical impulses to travel up the optic nerve, or the auditory nerve, or the olfactory nerve, or…well you get my point. It also takes a small amount of time for the synapses in your visual cortex, or your olfactory bulb, to collate and cross reference the information against your previous experience, and then finally it takes a further fraction of a second for that information to be served up to your consciousness as a perceptual sense. The point is…it all takes time. Not much time, but as with the consequence of the speed of light, the information being received by your eye is technically out-of-date by the time it reaches your consciousness.

OK, here it is. That process, like the speed of light itself, happens almost instantly…almost. It does take a certain amount of time for those little electrical impulses to travel up the optic nerve, or the auditory nerve, or the olfactory nerve, or…well you get my point. It also takes a small amount of time for the synapses in your visual cortex, or your olfactory bulb, to collate and cross reference the information against your previous experience, and then finally it takes a further fraction of a second for that information to be served up to your consciousness as a perceptual sense. The point is…it all takes time. Not much time, but as with the consequence of the speed of light, the information being received by your eye is technically out-of-date by the time it reaches your consciousness.

According to the Persian poet Ferdowsi, in his epic and ancient poem Shahnameh (which is considered to be entirely apocryphal), the man who invented chess submitted his new invention to the Persian King who was so impressed that he offered to reward the man with whatever he wanted. The man being a mathematician told the king that he wanted grains of wheat. Specifically, he wanted the wheat counted on a chessboard: starting in one corner of the board, he wanted one grain of wheat on the first square and two grains on the second square, then four grains on the third and so on, doubling the number of grains with each successive square. Now, you might think this a reasonable request, as the king certainly did, and he ordered an administrator to count out the wheat and award it to the man. The problem, which the king did not understand at first, is that the man was requesting an exponential progression of wheat, which, by the time you reach the final square on the board, would result in far more wheat than you might imagine.

According to the Persian poet Ferdowsi, in his epic and ancient poem Shahnameh (which is considered to be entirely apocryphal), the man who invented chess submitted his new invention to the Persian King who was so impressed that he offered to reward the man with whatever he wanted. The man being a mathematician told the king that he wanted grains of wheat. Specifically, he wanted the wheat counted on a chessboard: starting in one corner of the board, he wanted one grain of wheat on the first square and two grains on the second square, then four grains on the third and so on, doubling the number of grains with each successive square. Now, you might think this a reasonable request, as the king certainly did, and he ordered an administrator to count out the wheat and award it to the man. The problem, which the king did not understand at first, is that the man was requesting an exponential progression of wheat, which, by the time you reach the final square on the board, would result in far more wheat than you might imagine.

Of the many posts on this website, some are more popular than others. Some topics seem to strike a chord with readers, or perhaps it’s my treatment of those topics that stir the hearts and minds of the few who happen across my work.

Of the many posts on this website, some are more popular than others. Some topics seem to strike a chord with readers, or perhaps it’s my treatment of those topics that stir the hearts and minds of the few who happen across my work. The EMF meter is, for those not already familiar, a device for measuring electromagnetic fields in the general proximity of the device’s sensors. Electromagnetic fields are everywhere, quite literally. Our environment, that is the entire planet, is inundated with waves of energy. The most powerful come from our sun, most of which is absorbed by our atmosphere, but everything that uses electricity in any way also generates an EM field. Electromagnetic energy is a form of radiation and it is measured along a spectrum – the electromagnetic spectrum – which includes at its extreme ends: Gamma radiation and ELF waves (extremely low frequency). Along the spectrum between Gamma rays and ELF are frequencies that correspond to radio waves (which includes cellular signals and other communications transmissions) and even the light spectrum that we’re able to detect with our eyes (the visible light spectrum).

The EMF meter is, for those not already familiar, a device for measuring electromagnetic fields in the general proximity of the device’s sensors. Electromagnetic fields are everywhere, quite literally. Our environment, that is the entire planet, is inundated with waves of energy. The most powerful come from our sun, most of which is absorbed by our atmosphere, but everything that uses electricity in any way also generates an EM field. Electromagnetic energy is a form of radiation and it is measured along a spectrum – the electromagnetic spectrum – which includes at its extreme ends: Gamma radiation and ELF waves (extremely low frequency). Along the spectrum between Gamma rays and ELF are frequencies that correspond to radio waves (which includes cellular signals and other communications transmissions) and even the light spectrum that we’re able to detect with our eyes (the visible light spectrum). It’s really as simple as this: there are many possible causes of EMF fluctuation in a given space, and as long as there is doubt about what caused the reading, it cannot be attributed to any one phenomenon.

It’s really as simple as this: there are many possible causes of EMF fluctuation in a given space, and as long as there is doubt about what caused the reading, it cannot be attributed to any one phenomenon.

If you spend any amount of time on the internet, particularly Twitter, there’s a good chance you’ve seen this meme image. (Right)

If you spend any amount of time on the internet, particularly Twitter, there’s a good chance you’ve seen this meme image. (Right)