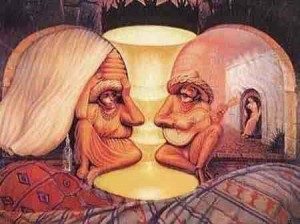

Figure 1.

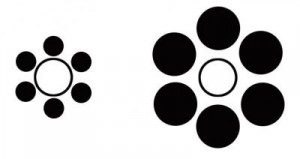

Here are a few demonstrations of just how easy it is to fool the sophisticated perception devices that our so-called big brains use to interpret and reconcile the enormous amounts of conceptual data we experience every day of our lives. Both figures one and two are common and well known optical illusions, though are they really optical? And are they really illusions?

Few would doubt that either is just a simple confusing of spatial geometry and/or language norms, but is this really the fault of our optic systems, or is it more indicative of a problem seated deeper inside our minds?

Figure 3.

FINISHED FILES ARE THE RE

SULT OF YEARS OF SCIENTI

FIC STUDY COMBINED WITH

THE EXPERIENCE OF YEARS…

In the above passage, the letter “f” is used a specific number of times, though almost without fail, when one tries to count them out, the outcome is wrong.[1] Even when the reader is familiar with the word play, they will still end up with the wrong number more often then not. Is this because people are inherently dim? Is it because they lack a certain level of attention to detail? Or is it simply another trick of perception brought on by our brain’s ability to filter information?

Figure 4.

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.

The above jumbled paragraph (figure 4.) is actually a part of a Doctoral Thesis from Nottingham University in 1976, by Graham Rawlinson Ph.D.[2] Dr. Rawlinson found, through a series of cognitive experiments intended to shed some light on the process by which we, as a species, learn to read, that letter placement within a word is largely irrelevant to both the word’s meaning, and to our ability to quickly decipher the word against the backdrop of a complete sentence.

If a word is jumbled on its own, that is without the context of supporting words in a sentence or paragraph, then our ability to discern its meaning is drastically reduced or completely eliminated, but within the context of a sentence, our ability to understand the sentiment of the language is completely unaffected by the placement of the letters.

Figure 2.

Contrary to what some may be thinking, this does not mean that we are all linguistically psychic, what it means is that our brains rely more on context than on detail. We derive meaning from patterns, such as language, by interrelating common characteristics and applying them to previous experience, resulting in unique interpretation of characteristics that may be historically similar, but are contextually independent. But in the case of language, we have cause to find meaningful patterns in what may sometimes seem like complete chaos. Language is, by definition a static pattern of visual, auditory and (most importantly) conceptual characters.

What this demonstrates, though somewhat clumsily, is that our cognitive powerhouse brains are specifically evolved to do exactly what many in the paranormal research field claim will be our downfall (myself included). Quite often we use large, generalising terms to describe what is ultimately, a biological necessity for our existence; confirmation bias, belief building, tunnel vision, autosubscription and even to some extent autodebunking.[3]

There are two specific psychological processes that are normally to blame for a great deal of both the autodebunking and autosubscription going on within the paranormal community; Apophenia and Pareidolia. Either idea, while seemingly similar in definition, is responsible (at least in some part) for a large percentage of paranormal phenomena; from hauntings, to poltergeist, to EVP and to orb photography, and to religious and pseudoscientific ideologies.

Apophenia is often considered a symptom of schizophrenia and autistic spectrum disorders, though we all suffer from apophenic influences on a much more regular basis than a great many people would be comfortable with.[4] Pareidolia on the other hand, is probably the most underrated and oft lamented ability our brains hold.[5] Together, these ideas are the foundation of the cognitive interpretation of what you and I might call…reality. Without these two concepts, or moreover, the processes underlying these concepts, we would not be able to perceive our world.

Here though is the important idea to consider; the underlying processes, of Apophenia and/or Pareidolia are really just symptoms of a larger condition. A condition, as I call it for lack of a better term, whose main function is to make sense of this strange thing called life. The mind is continually bombarded with information throughout the day and night, no matter our state of consciousness, no matter our level of attention and no matter our personal propensity for intellectualism or ignorance. We are bound to a life of sensory overload, or at least we would be had we not developed the ability to make sense of the things we see, hear, feel and well…sense, in a much more efficient way.

While you sit, reading this paper, wherever you might be and in whatever environment you find yourself, there is an almost unfathomable amount of sensory information being presented to you, millisecond by millisecond. Somehow, through the miracle of cognitive interpretation, you are able to make sense out of that macrocosm, by way of consciously selecting what information is important and what is irrelevant. At least, you may think it’s a conscious process.

The human mind, as a computational device, has been studied by many in terms of its memory capacity, in comparison to the basic software requirements for cognition. Some early studies have given us numbers correlated to computer bytes, suggesting that the human brain is capable of retaining up to 1020 bytes of information, though later estimates have reduced that number to a range between 109 and 1013 bytes, which is little more than a few hundred megabytes.[6] If you can quell that rising sense of righteous indignation for a moment, you can see how poignant that earlier idea of prioritising the perceptual information we’re inundated with really is.

So, this perceptual trickery is really a symptom, or rather a feature, of the efficient nature of our brains. Subconsciously, our cerebral cortex processes all of the countless bytes of information we encounter over the course of a day. But our reality is finite, we haven’t the time or the ability to consider, consciously, every piece of sensory information we perceive. We must, in as efficient a manner as possible, discover what is important and what is not, and consequently, we must subconsciously consider the context of all that data in order to determine what is important.

If we cannot consider all of the information we perceive, but we must discern what is relevant, then we must develop a process, a set of rules about what information to consider and what to disregard.

Herein lies the problem however; during that process of enacting, applying and adapting perceptual rules, our environment changes. It changes drastically, requiring that we adapt and change and understand those changes, and it is this process of adaptation that gives us this unendingly unique ability to see pattern, where pattern doesn’t necessarily exist.

From a survivalist’s perspective, in a world filled with threats to that survival, it will always be a better thing to err on the side of caution. To see threat where it may or may not exists, rather than to not see threat where it surely does exist. For this reason, our brains are hardwired (so to speak) to scan the information we perceive quickly, applying it to the various sorting rules we’ve evolved, and whenever a set of environmental conditions fits, even remotely, to any previously experienced situation, we automatically accept it as a fact of reality, whether it truly is or not.

And it is the above idea that brings this discussion full circle and applies it to the world of paranormal research. The processes or concepts involved in Apophenia and Pareidolia are often blamed for the misidentification and misinterpretation of some of the strangest phenomenon we can encounter in our world, but really, these ideas are just a symptom of a larger perceptual problem. What we see, hear and feel, are not always to be trusted. What we know to be true through deduction and reason can, more often than not, trump what we think we see and hear.

Everywhere in our world, our eyes and ears are tricking us, and more so when we delve deep into the mysterious things of our world; we cannot trust the things we know by sight and sound alone, we must quantify and verify the ideas we come to accept and know for certain; we must ensure that those ideas have not been corrupted by perception. Those common ideas of paranormal pseudo-fact (EVP, apparitions, ghost photography just to name a few) remain unquantifiable and completely unverified, and in so much as they may be caused by unseen and unknown energies, until such time as human fallibility of perception can be eliminated as a cause, caution should be used wherever possible, in the labelling, interpretation and dissemination of these ideas.

In short, beware what your eyes and ears tell you, for they are known to be liars.

[1] Believe it or not, there are six F’s in the passage

[2] See Dr. Rawlinson’s Thesis here: http://opentype.info/static/Letter-Position-in-Word-Recognition.html

[3] Autodebunking is a term coined by Matthew Didier of the Paranormal Studies and Investigations Canada group to describe those who dismiss out-of-hand any evidence to support new and untested theories regarding typically paranormal topics without due attention, and simply based on prejudices of belief alone. In the case of autosubscription, I have simply expanded the above idea to include what might be considered the antithesis of Mr. Didier’s term.

[4] For an easy to understand explanation of Apophenia, see the Wikipedia entry: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apophenia

[5] A simple explanation of Pareidolia can also be found via Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareidolia

[6] One of many studies completed on this issue is nicely summated by Ralph C. Merkle: http://www.merkle.com/humanMemory.html