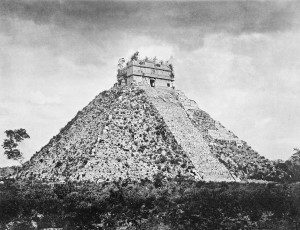

With all of the pyramids around the world, it seems clear that the ancients had an affinity for lasting architecture. They built things to withstand the winds of time. At least, they built certain things to last. Temples, tombs, ceremonial chambers and all kinds of sacred sites litter the landscape all across this planet, each one from an age lost to antiquity. Often, though, what didn’t survive alongside these megaliths, was any notion about what they were, why they were built, or how they were built. Sure, scholars are relatively certain that they’ve deciphered lost texts and cryptic hieroglyphics, and thus believe they have a decent grasp on answers to those questions, but there are many people who don’t agree that conventional wisdom in this regard is all that solid.

With all of the pyramids around the world, it seems clear that the ancients had an affinity for lasting architecture. They built things to withstand the winds of time. At least, they built certain things to last. Temples, tombs, ceremonial chambers and all kinds of sacred sites litter the landscape all across this planet, each one from an age lost to antiquity. Often, though, what didn’t survive alongside these megaliths, was any notion about what they were, why they were built, or how they were built. Sure, scholars are relatively certain that they’ve deciphered lost texts and cryptic hieroglyphics, and thus believe they have a decent grasp on answers to those questions, but there are many people who don’t agree that conventional wisdom in this regard is all that solid.

All this confusion (though either side of the argument will tell you they aren’t confused at all), stems from one single aspect of ancient architecture, and that is that we have to guess at their significance. Whether we’re on the mark with that guess or not, we will still never know for certain that we’re right. These buildings and monuments that were built as long as 5000 years ago (or older, in some cases) are enigmatic shadows of cultures past, but what will happen in another 5000 years?

Will our legacy civilizations be just as perplexed by the purpose and significance of our buildings, should any survive that long? Will they argue amongst themselves about whether we had the technical expertise and engineering prowess to construct the wonders of our ancient time?

Will our legacy civilizations be just as perplexed by the purpose and significance of our buildings, should any survive that long? Will they argue amongst themselves about whether we had the technical expertise and engineering prowess to construct the wonders of our ancient time?

Perhaps not. Record keeping is the primary mitigator in this war of attrition. Most of the records we use to study ancient culture and architecture are fragments of texts written in lost languages, and our understanding of their meaning is pieced together through a process of comparison to other better known artefacts. Our records, it could be argued, are much more complete and decipherable than those of ancient cultures. At least they are now, but who’s to say what will happen over five millennia or more?

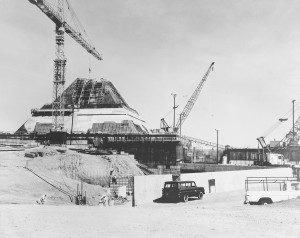

In a strange parallel to the pyramids of old, there are similar structures, built in recent years, with modern technology, and for modern purposes, that might serve as a future analogue to the questions posed above.

In the early 1970’s, as a part of the United States Army Safeguard anti-ballistic missile program, the US military built an early-warning detection and defence compound near Grand Forks, North Dakota. The facility, known as the Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, achieved operational status on September 28, 1975, but its lifespan was short lived. It was decommissioned on February 10, 1976, less than a year after it all began.

The site consists of the large pyramid shaped building, which was the missile control building and PAR “backscatter radar” station, as well as 100 ICBM-launcher inside some 70 missile silos, and some service buildings. There is a vast underground tunnel network associated with the site, which was flooded following its decommissioning, presumably to discourage unauthorised use.

The SRMSC has sat empty, in the wastes of North Dakota for nearly four decades, unused and untouched. It is a ghost of the cold war and of our government’s fear of intercontinental attack by competing world powers, but it lays there, impotent and broken, and when you look at pictures of this vestige of our military past, it’s hard to miss the resemblance to certain ancient megalithic sites.

Those similarities, while striking, are superficial, but will the effect such structures have on the imagination of future archaeologists be any different if records of its construction and use don’t survive the ages? Can you imagine a group of wide-eyed tourists walking among the monolithic buildings, gazing at the huge pyramid in the distance, wondering why it was built and what it meant to those who used it? Will future curiosity seekers marvel at our advanced understanding of radar technology, electronics, and ballistics? Will some element of their society cling to the notion that we were more – or less – than their own conventional wisdom suggests?

Cultural evolution progresses at a startling rate; in a matter of 300 years, whole language systems can become almost unrecognisable. Iconography becomes distorted and knowledge bases shift between world powers. War, emigration, social and financial collapse, natural disaster, all of these things could change the course of our cultural evolution en-route to unimaginable places in the future, and once our progeny reach their destination, will they recognise what they see behind them, or will they be just as baffled by their past, as we are by ours?

Cultural evolution progresses at a startling rate; in a matter of 300 years, whole language systems can become almost unrecognisable. Iconography becomes distorted and knowledge bases shift between world powers. War, emigration, social and financial collapse, natural disaster, all of these things could change the course of our cultural evolution en-route to unimaginable places in the future, and once our progeny reach their destination, will they recognise what they see behind them, or will they be just as baffled by their past, as we are by ours?

The SRMSC is named after a US Military hero, the former commander of the US Army Air Defense Command, Lieutenant General Stanley R. Mickelsen. He enjoys a certain renown among military historians as the force behind the US air defense artillery’s development from an era of guns to an era of missiles. Of all the ways such a man’s legacy could have been carried into the future, joining the Mayan chiefs and Egyptian Pharaohs as a historic character forever tied to an enigmatic monument may not have been in the original design plan.